Posted 14 October 2020

On the 5th August 1858, (on the third attempt) the first undersea transcontinental telegraph cable was laid. The British ship HMS Agamemnon and the American USS Niagara met in the middle of the Atlantic ocean, connected two ends of the cable, and together laid the cable from Newfoundland to Ireland. It was a simple affair with seven copper conductor wires, wrapped with three coats of the new wonder material, gutta-percha (or as we know it today, rubber). This was further wrapped in tarred hemp and an 18-strand helical sheath of iron wires, the cable itself took four years to build.

On the 16th August it carried the first “official” telegraph message sent by Queen Victoria to U.S. President James Buchanan, the 509-letter message took 17 hours and 40 minutes to arrive. Sadly the cable lasted for just three weeks, to overcome a weak signal, the power was turned up too high, and it was destroyed.

It took six years before another cable was laid so telegraph messages could cross the Atlantic again. In 1866 Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s SS Great Eastern was the ship that laid the first lasting transatlantic cable. At that time it cost £20 to send a 20-word telegram – a third of the annual salary of a fisherman in Newfoundland where the Atlantic Cable landed. By 1900, there were over 130,000 miles (200,000 km) of cable running along the ocean floor, but the cost to send a message was still unreachable for most.

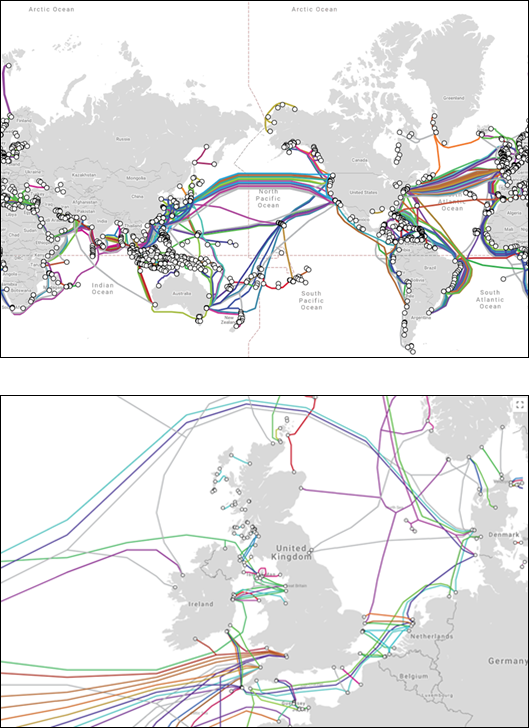

It took six years before another cable was laid so telegraph messages could cross the Atlantic again. In 1866 Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s SS Great Eastern was the ship that laid the first lasting transatlantic cable. At that time it cost £20 to send a 20-word telegram – a third of the annual salary of a fisherman in Newfoundland where the Atlantic Cable landed. By 1900, there were over 130,000 miles (200,000 km) of cable running along the ocean floor, but the cost to send a message was still unreachable for most.For all the talk about the 'cloud', practically all of the data shooting around the world actually relies on the series of undersea cables (most of them the width of a garden hose) to get around, a massive system of fibre optic cables lying deep underneath our oceans. Today those cables carry 95 percent of daily worldwide communications, plus they carry financial transactions worth over $10 trillion a day.

The first fibre optic cables were developed in the 1980s, and the first fibre optic transatlantic telephone cable was TAT-8, which went into operation in 1988. Today's fibre optic cables have their fibres arranged in a self-healing ring to increase redundancy, and their submarine sections follow different paths along the ocean floor. Where these undersea cables come ashore are called "landing areas,“ some systems have dual landing points.

Cables can be broken by ship's anchors, fishing trawlers, earthquakes, currents, and even *shark bites (*not really, that’s just a myth). After 1980, many cables were buried, but that didn't stop significant breaks from happening. To repair cable, repair ships either bring the entire cable to the surface or else they cut the cable and bring up only the damaged portion. Then, a new section is spliced in.

Today, there are around 430 submarine cables in service, stretching over 750,000 miles (1.2 million km) around the world. One of the deepest is a cable between Japan and the U.S. is about 8,000 meters below sea level (in the Japan Trench). That's almost as deep as Mount Everest is high!

Today, there are around 430 submarine cables in service, stretching over 750,000 miles (1.2 million km) around the world. One of the deepest is a cable between Japan and the U.S. is about 8,000 meters below sea level (in the Japan Trench). That's almost as deep as Mount Everest is high!So-called new technology has in this case not overtaken the old. In fact, as little as 3% of global communications are carried via satellite, which means 97% of the world's communications are transported around the world via fibre optic submarine cables. The problem is that satellite transmissions suffer from latency and loss whilst optical fibre can transmit at 99.7% of the speed of light. The only people watching Netflix via satellite are researchers in Antarctica.

Antarctica remains the only continent not connected by a submarine telecommunications cable. Due to a sparse population and ice shelf movement up to 10 meters/year, it’s a very challenging environment. Fibre optic cable there would have to withstand temperatures of -80 degrees C (-112 degrees F).

Over the past decade American tech giants started taking more control. Google has backed at least 14 cables globally. Amazon, Facebook and Microsoft have invested in others, connecting data centres in North America, South America, Asia, Europe and Africa, according to TeleGeography, a research firm. If you’re interested, this interactive map from TeleGeography shows undersea data cables which span the Atlantic Ocean and around the world.